|

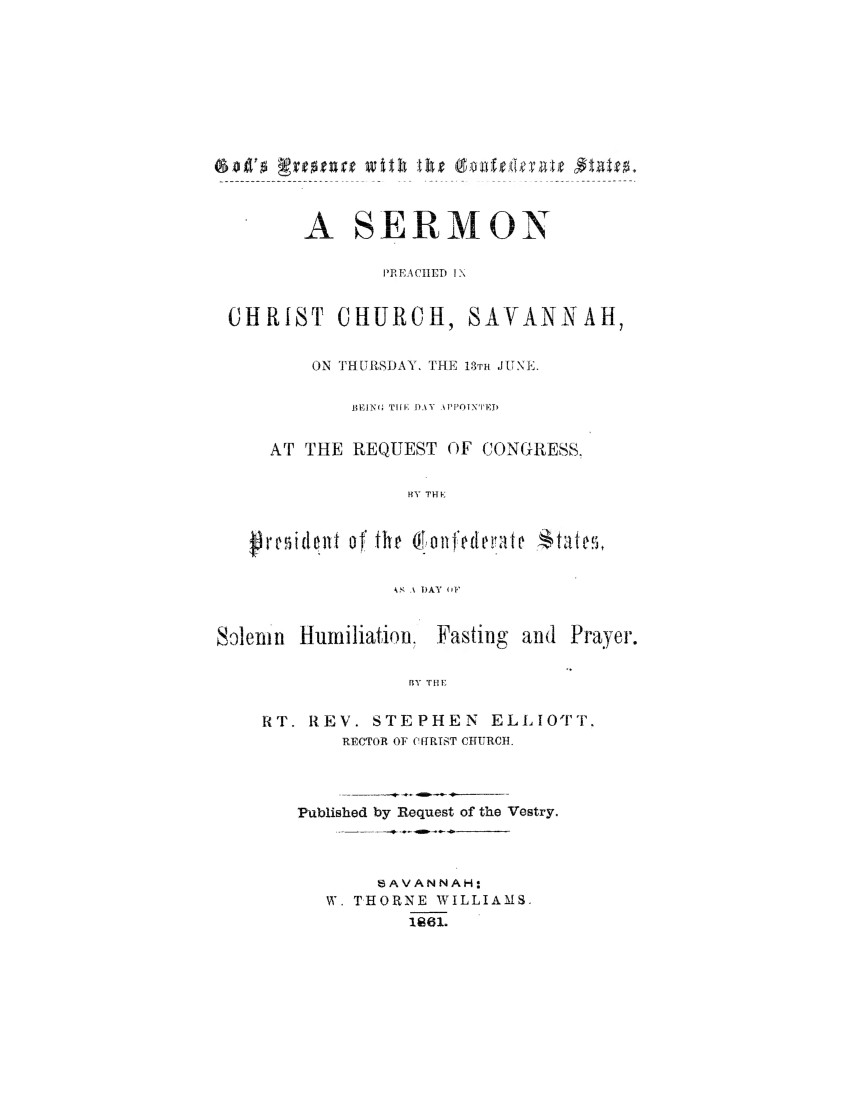

Psalms

115: 1, 2, 3.

Not

unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give

glory,

for thy mercy and for thy truth's sake.

Wherefore should the heathen say, Where is now their God?

But our God is in the Heavens: he hath done whatsoever he

pleased.

The

devout

Proclamation of our President invites us to give, to-day, a public

manifestation of our gratitude for the clear proofs of the Divine

blessing

hitherto extended to the people of the Confederate States in their

efforts to

maintain and perpetuate public liberty, individual rights and national

independence. At the same time it calls

upon us to humble ourselves

before God in this our time of peril and difficulty, to recognize His

righteous

government, to acknowledge His goodness in times past, and to

supplicate His

merciful protection for the future. It

is a day to be devoted to mingled gratitude and humiliation—to

thanksgiving for

great mercies and to a confession of our unworthiness of them—to

acknowledgment

that unto Him alone belongs the glory of our present condition, and to

supplication that he will continue to be our shield and strong tower of

defence. This direction which the

Proclamation of our

Chief Magistrate has given to the devotions of the day will require a

review of

our civil affairs from the commencement of our constitutional struggle,

in order

to point out to you the overruling and directing hand of God in all our

movements. May His Holy Spirit rest upon

me and preserve my pen from bitterness and my tongue from evil

speaking, and

may that same Spirit enlighten your minds to perceive His presence in

all that

is past, and sanctify your hearts to keep it there through all that is

before

us.

For

many years past, God has

permitted us, as a people, to be deeply humiliated.

While we have enjoyed great material

prosperity and have, in a certain sense, maintained our position under

the

forms of the Constitution, we have been systematically slandered and

traduced,

in public and in private, at home and abroad, in a way such as no free

and independent

people has ever before so quietly submitted to. Because

of the maintenance of an institution inherited from our fathers,

which the rest of the world was pleased to consider as incompatible

with

civilization and with Christianity, we have been made, thro’ every form

of

literature, a by-word among the nations of the earth.

The lecture room, the forum, the senate

chamber, the pulpit, have all been used as the instruments of our

denunciation. The newspapers of the

Northern States and of

Europe have vied to express their abhorrence of our social life and

their

contempt for ourselves. The grave

statesman,

the flippant poet, the sentimental novelist, the critical reviewer, the

witty

satirist, has each, in turn, singled out our homes as the targets of

his

falsehood, and our mothers, and wives, and daughters, as the objects of

his

insult. In many of the religious bodies of

the United States, their communicants from the slaveholding States were

excluded from the participation of the sacrament of the Lord's Supper,

and the

Southern ministers from brotherly interchange of services.

We had committed an unpardonable sin in doing

what Abraham, the friend of God, had done, what Philemon, the clearly

beloved

fellow laborer of Paul the aged, had not been ashamed to do. All this abuse and misrepresentation was

borne according to the temper of men, by some with the patience of

Christians, leaving

their justification in the hands of God, by others with contempt for an

hypocrisy which could see the mote in a brother's eye, but not the beam

in its

own eye; by not a few with arrogant defiance and words of bitter scorn. So far it had been a war of ideas, but

leaving, nevertheless, rankling wounds behind. Gradually

it passed from literature to politics, and we were soon made

aware that a deep laid scheme, resting upon the double basis of

fanaticism and interest,

was closing in upon us, which was to reduce to overt acts the ideas

which had

been so assiduously impressed not only upon the minds but upon the

feelings of

a whole generation. We were to be

humbled, not simply by being held up to the scorn of the noble and

generous all

the world over, but by being virtually disfranchised, even while

retaining the

forms of constitutional liberty, and being permitted to keep up the

appearances

of equality. This scheme was devised by

a far-seeing statesman, now occupying a position of commanding

influence, who

laid his plans with consummate skill and has pursued them, lor twenty

years,

with undeviating firmness, thro’ good report and thro’ evil report. He advanced from point to point with the

steady pace of inevitable destiny, drawing his lines closer and closer

around his

fluttering yet unresisting victim. He

educated through the Press and through the Pulpit, a whole generation,

and the

two ideas which he has made the ideas of the times, are the

irrepressible

conflict, under democratic institutions, between freedom and slavery,

and the

utter inability of slavery to maintain itself in the face of freedom. The one idea combined into a great party the

fanatic, the laborer, the foreigner, the farmer, the manufacturer—the

other

idea gave confidence and fearlessness to his followers.

When this powerful and ever growing host was

thoroughly prepared for its work, he decided, after a calm survey of

all the chances

of the conflict which he was about to inaugurate, that success was

inevitable. He perceived that there was

but one movement

that could defeat his plans— a dissolution of the Union—and he

maintained that

to be an impossibility. He believed that

party divisions could keep the South so distracted—could separate her

statesmen

by such lines of bitterness—that no combined resistance to his sure but

stealthy

advances, could ever be brought about. Had

all his followers been as prudent as himself, and had not God been on

our side,

nothing could have saved us from slow but inevitable destruction, for

it was

not his purpose to strike any blow that might alarm or arouse the

south, but to

achieve all his purposes thro’ seemingly constitutional movements. He well knew that the rapid growth of free

territory, filling up with a foreign population of the most radical

description,

would surely give him what he aimed at, and that gradual changes in the

Constitution

or plausible interpretations of it would cover all his advances with

the forms of

law, and render any opposition difficult which proceeded beyond the

limits of

legislative or judicial resistance, of which he had no fear. And then he looked upon the section he was

devoting

to ruin and perceived that she was engaged in a fierce Presidential

strife even

while he was closing his toils around her, well might he have supposed

that his

game was a sure one and that time only was needed to make his triumph

complete. At this moment, in the

confidence of his

heart, he might well have asked “Where is now their God?” and our

answer could

only have been “Our God is in the Heavens; he hath done whatsoever he

pleased.” But just at that moment, when he

considered

us deserted and doomed, commenced a series of events which has brought

us this

day to the altar of the living God to ascribe the glory of our

deliverance not

to ourselves but to Him, to confess our unworthiness of all this

unmerited

goodness and to pray him to continue to bless the work which he has

thus far so

graciously favored—"Not unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name

give

glory, for thy mercy and for thy truth's sake.”

By

that mercy of God our greatest

difficulties have been successfully passed through, I do not say our

greatest

privations or our keenest sufferings. We

may yet have before us years of self-denial and of self-discipline—we

may be called

to suffer in our fortunes and in our homes—our chambers may be clothed

in

mourning and our hearts may be lacerated with sorrow, and yet, with all

this it

may be true that our greatest difficulties as a nation have been

already met

and overcome. The severest trials

through which a movement, such as ours, is forced to wade, are those

which arise

in its inception and in its organization. The

work which we had undertaken to accomplish was in many respects a

novel one. It was not a revolution

against intolerable ills—it was not the casting off of a foreign

tyranny which had

ground us to the dust—it was not even rebellion against the forms of

the

government under which we had lived, that we might substitute for them

other

forms, but it was the withdrawal from an Union, which had given us, in

spite of

its abuse and corrupt administration, a large share of material

prosperity and

social happiness, and which was associated with all our anticipations

of

national greatness. The love of the

Union was deeply ingrained into the hearts of the nation, and into no

part of

it more deeply than our own Southern section. We

were proud of it as that which gave us dignity abroad and advancement

at home. The people considered its

freedom to be the envy of the world, its constitution the “ne plus

ultra” of

political wisdom. Our most prominent

statesmen had held it up before the nation as the bond of our greatness

and as

the hope of the human race. Webster

had consecrated it, in the Northern mind, by that master piece of

eloquence

which, as a rhetorical effort, has not been surpassed in ancient or

modern

times. Clay

had surrounded it with all the charms of his fascinating personal

popularity,

and had identified it, all through the West, with his wide-spread

political

opinions. Jackson had added to the

influence of this idol of the West,

the idea that the Union had been once preserved by him and that, he had

left

its continued preservation as a sacred legacy to his followers. Even Calhoun,

while advocating the doctrines of State sovereignty, had pressed them

most

earnestly as the means whereby alone the Union could be maintained. But above all, Washington-—the

personification of American constitutional

liberty—had committed it, in his dying words, to the people, as the

central idea

around which the future should forever revolve. It

seemed impossible ever to overcome this idea, and yet the question

had become one, in the minds of many, no one knew how many, between the

Union

and a passive subjection to the yoke which had been so skillfully

preparing for

our necks. Again and again had disunion

been attempted and had failed, in some cases, with ignominy, with

hopelessness

in others. The Union was fast absorbing

everything in the popular mind and becoming the devouring idol of the

nation. Before it the constitution had

changed its

whole scope and meaning—before it liberty was fast becoming a mere

word—under its

sanction an irresponsible majority was transferring power, prosperity

and

wealth from one section of the country to the other.

The cry of Union had become a sanction for

every irresponsible decree, a war-cry against all opposition that

promised to

be effectual. The greatest danger of the

South was, lest her people should permit this idea to overlay every

other

consideration and to rise superior to every constitutional infraction. There was no overt act of tyranny to arouse

the

people to madness—no action on the part of the government to render

resistance

immediately necessary—nay, the government had, in a certain way, been

in the

hands of those who were willing to concede to the South her

constitutional rights. It was necessary to

meet the deeply laid and

far-reaching scheme of which we spoke just now, by an equally

far-seeing and

prospective opposition, and the difficulty was lest the people should

not see,

with any degree of unanimity, the necessity for immediate action. All saw that the time was coming—all looked

shudderingly at the prospect of civil convulsion which seemed drawing

nearer

and nearer—but Hope was strong in many of our most devoted Southern

hearts—men

who are now standing with their swords in their hands and their shields

clasped

over the bosom of their mother in the very front rank of battle—that

God might

yet avert the evil and postpone if not defer forever the stern

necessity. Secession was urged more upon

what was before

us in the future, than upon what had actually taken place.

Coming events had, to be sure, cast their

ominous shadows before, but as yet there was no act which had come

directly home

to the cottage and fireside. The raid

into Virginia in 1859, had, at the time, produced a deep sensation, but

as that

Mother of States had treated it lightly herself, having been satisfied

with the

punishment of the wrong-doers, it had died away. Under

these circumstances, the most sanguine

feared the issue of the question between Secession and the Union. They believed that a majority in certain

States would sanction an act of separation, but they dreaded such an

opposition

in each State as might neutralize the action and impair its whole moral

effect. Anything like a nearly equal vote

in the

States would have created a nucleus of opposition which would have

rendered the

whole proceeding inefficient. But, thanks

be to God he gave us among ourselves a more remarkable unanimity than

anyone

had dared to hope for, and what was lacking in ourselves, was supplied

by the

blunders of our adversaries. Instead of

supporting those who were not prepared for separation, by granting

their

moderate demands of constitutional amendment, they struck blow after

blow upon an

already over excited country, with a folly that was inconceivable. Every plank upon which the Union men of the

South

desired to stand, was successively struck from under them, and the

unanimity

which the merits of the question failed to produce, their stubborn

obstinacy

rendered inevitable. Instead of meeting

the advances of the Union men of the South with a lofty magnanimity—a

magnanimity which a victorious party can always afford to exhibit—they

met them

with a. defiant arrogance.

They showed evidently by all their actions

that they considered the struggle as at an end, and that they were

commissioned

to walk as conquerors over a subjugated territory.

One by one, all their friends were driven

from them, and thus has been produced an Union of the South which was

scarcely

hoped for when the struggle first began. And

thanks be to God their folly still continues, and if, with humble

hearts, we bow ourselves before God, and ascribe this important result

not to

ourselves but to His overruling and protecting Providence, we shall see

still

greater wonders worked for us, and new stars rising to take their place

in our

constellation, and nations coming to our aid who were supposed to be

bound to

the North by strong bonds of sympathy and fanaticism.

“Not unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy

name give glory, for thy mercy and for thy truth’s sake.”

Another

danger which threatened

us and which is the “experimentum crucis” of all new nationalities, was

the

adoption of the permanent constitution under which we were to live. It is always a moment of critical peril. It was the rock upon which Cromwell's

successful usurpation crumbled to the dust. So

long as he lived, his genius sustained the civil arrangements which

he had substituted for the English constitution, but with his death

things

flowed back into their ancient channel and the nation returned joyfully

to the monarchical

government even of the Stuarts. It was

the rock upon which the European revolutions of 1848 all split. Theorists took up the question of government

and inexperienced professors and fantastic poets were deputed to

arrange

constitutions and to mould the necessities of a practical world. It ended just as any man of common sense might

have foreseen that it would end, in the usurpation of a clear-headed

man of

practical experience. In the formation of

the constitution of 1789, that which we have just amended, there was

large

diversity of opinion, and much time was consumed ere it could be made

satisfactory to the thirteen States. The

leading men of the country were forced to exert all their influence to

secure

its adoption. Washington talked for it— Madison

and Hamilton and Jay wrote for it—the heroes

who had

illustrated the war of the Revolution, prayed for it as the seal to

their bloody

triumph. And yet, with all this array of

influence, it was very reluctantly adopted by several of the States,

and one

distinguished gentleman of South Carolina said, during the debates upon

its

adoption in the Convention of that State, “I desire no other epitaph to

be

written upon my tomb than this: ‘Here lies the man who voted against

the

adoption of the Federal Constitution.’” How wonderful then, that in a

few weeks

a Congress of gentlemen, who had differed all their lives upon

questions of

national policy, who were just warm from heated discussions of

principles as

well as men, who were yet reeking with the sweat of one of the

bitterest

Presidential elections which had ever distracted the country, should

have

submitted to the people of the Confederate States a constitution of the

most

conservative character in which many grave errors of the old

constitution had

been amended and new features introduced of the highest moral and

religious

import. They entered that Congress with

several questions ominous of evil pressing upon them—questions upon

which, if

they had erred, their cause must have been shaken to its centre. Among these were the re-opening of the

African slave trade, the change in the value of slave representation,

and that

question which had once before disturbed the Union, the proper scale of

duties

upon imports and exports. A false step

upon any one of these three questions would have been, in our then

condition,

almost irretrievable. The reopening of

the African slave trade would have disgusted Europe and produced great

dissatisfaction at home. A change in the

value of slave representation would have disaffected that large

population of

our mountains and pine barrens who own no slaves, and would have thrown

them at

once into the hands of demagogues. Too

high a tariff would have checked the sympathy of England and France,

and too

low a tariff would have forced us to resort to direct taxation, which a

people must

be educated to bear. Marvelous then was

it in our eyes that these gentlemen should have laid upon the altar of

their

country all their private views and all their public differences, and

should

have adjusted every point with such nice discrimination, with such wise

and Christian

moderation, with such a happy conception of the necessities which

surrounded

their States, that an almost unanimous shout of applause should have

arisen

from a delighted constituency. And

afterwards, that seven conventions, composed in a like manner of men of

every

shade of opinion and of every party in politics, should have so quietly

and so

unanimously accepted their work, can be attributed to nothing else but

the overruling

spirit of God. All these bodies entered

upon their duties with fasting and prayer—they all acknowledged God

every day

in prayer—they placed him in the forefront of their constitution, and

they

recognized him as the supreme ruler of the universe, and we therefore

can truly

say again “Not unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give

glory, for

thy mercy and for thy truth’s sake.”

The next trial, through which

the

Confederate States were called upon to pass, arose out of the

regulation of its

financial affairs. Napoleon is reported

to have said, blasphemously enough, that battles were decided by the

heaviest

artillery, and the world is fast coming to the conclusion that the

longest

purse is the arbiter of war. Granting

this to be in some measure true, we yet acknowledge most humbly the

presence of

God with our Government in this most important matter. The most

arrogant boast of the North was of its

own abounding wealth and of our exceeding poverty, and so long had this

assertion been made and so persistently had it been adhered to, that

both sides

were fast becoming to believe it. The

North and the South were both losing sight of the unalterable

principles of

political economy and had become confused amid the complications of

commerce

and trade and exchange. In a conflict

like this, wealth must be looked at from a different stand point from

that in

which it is viewed in a time of peace. At

its commencement, the North has most accumulated money, because its

great

cities have been the converging centres from all parts of this widely

extended

country, but accumulated money is very soon expended in a war like

this, and

the ability to continue it will depend far more upon the available

income of

each section than upon its money capital at the outset. The

wealth of the North depends upon

manufactures, upon trade, upon commerce, and the North West furnishes a

very

abundant supply of food. Analyze this

wealth and you will perceive that its results depend upon the ability

to find consumers

and to furnish an exchangeable value upon which to trade. Unless

manufactures find a market, they

remain a drug upon the hands of the manufacturers and are a loss

instead of a

gain. Unless trade finds purchasers as

well as sellers, it very soon becomes bankrupt in the face of rents and

living

and the taxation of a war such as this will be, if it goes on.

Unless commerce has something to export as well

as to import, it must necessarily come to an end, for one cannot buy,

as the

world goes on now, unless he has something to sell. The North has

no great export of its own which

is a necessity to the world. Now and

then the failure of a grain crop in England or upon the Continent,

creates a demand

for corn, and then, for a season, the West can furnish a value that is

exchangeable. But this is an exceptional

case, and the commercial men of the North have never placed any

permanent

dependence upon it. It has rested its exchanges

upon the cotton and tobacco of the South, and it has obtained

possession of

these by flooding our States with its manufactures and nicnacs of every

description, and by acting as the commercial broker of the South.

And besides selling our valuable staple for

trifles like these, which we could as well make for ourselves, we have

annually

distributed much that remained of these staples upon hotels and

watering

places, in steamboats and railroads, in shops of luxury and temples of

fashion

and upon what is facetiously called education and accomplishments.

And by the time that the cotton and the

tobacco were made, it no more belonged to us than did the manufactures

of

England, and we were compelled in common honesty to let it go where it

was

really owned. At a very moderate calculation,

the exchangeable value thus furnished the North in return for its

manufactures and

its climate and its fashion, amounted annually to between one and two

hundred

millions of dollars. But all this is now

changed; we have seen the last of it, at least during the war, and a

year or

two will soon show that the subtraction of this amount from the one

side, and

the addition of it to the other, will make a marvelous difference in

the

aggregate of wealth. And while the

withholding of this immense sum of money from the North will cripple

its

resources, it will be put in circulation among ourselves and add to the

income and

resources of our own citizens. For there

is no truer principle in political economy than this, that the

distribution of

money has as much to do with the wealth of a country as its

production.

God seems to have endowed our financial officers

with the wisdom to seize the strong point of our economical position

and our

people with the patriotism to receive and adopt it. They have

made our great staple to supply for

them the place which gold and silver supply for the Banks. As

they issue paper money upon the coin which

they possess, so will the Confederate States issue paper upon the

cotton which

it will accumulate by the exchange for it of Confederate bonds, and

thus,

instead of a currency depreciating continually like the old continental

money,

we shall have a currency always at par, because the cotton which is its

basis,

is always wanted and receives no injury of any material consequence

from being

piled up during a blockade. If a

currency keeps at par, and it will always keep at par when it is known

to

represent an actual value, nobody will care to have it redeemed,

especially so

long as he may be hemmed in from intercourse with any except those

whose currency

it is. And besides furnishing a Bank

capital for the Confederate States, it becomes in the hands of the

government an

instrument of great power for the regulation and control of foreign

alliances. Refusing to permit its export except through

our own seaports, it will soon bring all the nations who use our

cotton, face

to face, with the question between us and our enemies. It is not

that cotton is King, but that God

has given our statesmen wisdom to use a great advantage aright, and the

people

self-denial to acquiesce in the arrangement, and to stand manfully by

it. “Not unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy

name give glory, for thy mercy and for thy truth's sake.”

And

in this very matter our God

does seem to have smitten our enemies with judicial blindness. Just when they most needed sound wisdom, they

have inaugurated a financial system which must cripple their resources. A prohibitory tariff, and one which they will

find it difficult to repeal, because it was given as a sop to

particular

States, just when a nation needs both friends and money, is the very

height of

folly, and a system of borrowing, at a heavy discount, is a poor

beginning for

a people boasting of its wealth and arrogant about its resources. The commercial men of the North perceive this

weakness and therefore it is that they cry out for quick measures and a

short

war. They know that they cannot bear a

long one, and very soon will they begin to murmur at any

Commander-in-chief who

desires to move slowly and surely, and will either hurry him into

measures which

will ensure his defeat or force him to yield his marshal's baton into

bolder

because more ignorant hands. Truly does

God

seem to have ordered everything for us and to have made everything work

for the

security of our cause. How can anyone

distrust him or be faithless enough to ask with our enemies, “Where is

now

their God?”

If

we turn from the financial to

the military affairs of the Confederate States, we perceive the same

visible

presence of God in our concerns. In the

beginning of this movement we appeared to have no resources wherewith

to meet

the immense preponderance of power that was against us.

They had armies, navies, armories,

manufactories, everything that could conduce to their

strength—fortresses

bristled in our midst and aimed their guns against the people they had

been builded

to protect—a large, well ordered army, stood upon our Texan frontier

quite in a

condition to have invaded and embarrassed us—a large armament was

fitted out to

strike at the heart of South Carolina, which was considered the soul of

the

rebellion—a navy yard of immense resources, filled with arms and

ammunition and

ordnance, supported by the strongest fortress in the Union and defended

by men

of war armed with guns of the heaviest calibre, lay upon our North

eastern

frontier. A hastily raised militia was

all we had to depend upon in the conflict. But

in a moment everything seemed changed in a

way more than natural. Skillful officers

sprang from every direction into the arena. Armed

men arose as if from the dragons teeth which the abolitionists had

been sowing for years. And fear seemed

to fall upon our enemies—unaccountable fear. Officers

who had never quailed before any living man—soldiers who had

borne the old flag to victory wherever it had waved over them—navies

which had

moved defiant over the world, all, all seemed paralyzed.

That large border army surrendered to militia

without a blow—that gallant armament, made up of the same fleet which

had run

in the revolution into the Thames, which had defied the Algerine

batteries,

which had brought Austria to terms in the Levant, which had spit its

fire into

the face of the almost impregnable fortress of St. Juan d'Ulloa stood

inert and

saw a gallant soldier, who was upholding their own flag, beaten out of

his

fortress by sand batteries and volunteers. That

immense navy yard, with its vast resources, with its great power of

resistance, with its huge fortress at its back? with its magnificent

men-of-war

all armed and shotted, was deserted in an unaccountable panic because

of the

threats of a few almost unarmed citizens and the rolling during the

night of

well managed locomotives. And nowhere

could this panic have occurred more seasonably for us, because it gave

us just

what we most needed, arms and ammunition and heavy ordnance in great

abundance. All this is unaccountable upon

any ordinary

grounds. But two days before a naval

officer of very high rank had reported to headquarters at Washington

that this

navy yard was impregnable. Is not this

very like the noise of chariots and the noise of horses, even the noise

of a

great host which the Syrians were made to hear when the Lord would

deliver

Israel? “And they said one to another,

Lo, the King of Israel hath hired against us the King of the Hittites

and the

Kings of the Egyptians, to come upon us. Wherefore

they arose and fled in the twilight and left their tents and

their horses and their asses, even the camp as it was, and fled for

their life.” “Not

unto us, Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give glory, for thy mercy

and for

thy truth's sake.”

And

now, my beloved people, after

such tokens of God’s presence with us in all the departments of our

civil

affairs, need we be afraid of man’s revilings, and man's threats? If God be with us, who can be against us?

Shimei’s cursings did not hurt David; they only returned upon his own

head. And if any be presumptuous enough,

in the arrogance

of their wealth and in the pride of their numbers, and in the

presumption of

their Pharisaism to ask “Where is now their God?” we can humbly answer

“Our God

is in the Heavens: he hath done whatsoever he pleased.” Nay,

more, we can tremblingly rejoice and

point to His presence with us upon earth. He

is too manifestly with our people, giving them unanimity and

patriotism—with our rulers, giving them wisdom and moderation and a

proper

sense of their dependance upon him—with our armies, shielding them in

the hour

of conflict, for us not to acknowledge it. We

should be as brute beasts before him if we did not perceive his

presence and humble ourselves before him. God

loves to be honored in the assemblies of the Saints, and he delights

in the praises and thanksgivings of his people. There

is no surer mode of driving Him from us than by refusing to

acknowledge His presence among us. It is

not humility to be blind to the tokens of God's goodness towards us, it

is

faithlessness—it is not vain boasting to enumerate his glorious acts in

our

behalf, it is giving Him the honor due unto His holy name.

Read the Psalms of David and note how

frequently he enumerates in long and elaborate verse the wondrous acts

of the

Lord, closing each stanza with the triumphant refrain, “For ins mercy

endureth

forever.” And surely he knew how God loved

to be praised. Let us not be afraid or

ashamed to see the hand of the Lord in everything, to believe firmly

that He

does manifest himself for the right, and to be a praying and a

thanksgiving

people, as well as a fighting people. “Some

trust in horses and chariots, but we will trust in the Lord our God.”

But

while we render thanks unto

the Lord for all His benefits towards us, how deeply should their

reception

humble us! For we have been utterly

undeserving of them. They are the tokens

of unmerited mercy. If God was only strict

to mark iniquity, which of us could stand? As

a people, how little have we done for his

cause! how poorly have we fulfilled the

great mission entrusted to our hands! What

wretched stewards have we been of the

treasures committed to our keeping! How

polluted our land has been with profaneness, with blasphemy, with

Sabbath

breaking, with the shedding of blood. What

violence and recklessness, what extravagance

and waste have manifested themselves as the normal condition of our

people!

what an idolatry to fashion has disfigured the ancient simplicity of

our people! What a high value has been put

among us

upon all those qualities which are the very opposites of the graces of

the

gospel, upon pride, upon self-reliance, upon animal courage! How inordinately has wealth been sought after

and valued! How honor, falsely so

called, has been exalted and almost deified! And

if with all these hateful sins cleaving to

our national skirts, God can yet manifest His presence with us, what

might we

not hope for, if we would lay down those iniquities at the foot of

Jesus’ Cross

and cry for mercy? Let us begin to-day

and with deep humility of spirit, confess our unworthiness and pray the

Lord

that He will not turn His face from us, but will still enable us to

say, “Our

Lord is in the heavens.”

We are engaged, my

people, in one

of the grandest struggles which ever nerved the hearts or strengthened

the

hands of a heroic race. We are fighting

for great principles, for sacred objects—principles which must not be

compromised; objects which must not be abandoned. We

are fighting to prevent ourselves from

being transferred from American republicanism to French democracy. We are fighting to rescue the fair name of

our social life from the dishonor which has been cast upon it. We are fighting to protect and preserve a

race who form a part of our household, and stand with us next to our

children. We are fighting to drive away

from our

sanctuaries the infidel and rationalistic principles which are sweeping

over

the land and substituting a gospel of the stars and stripes for the

gospel of

Jesus Christ. These objects are far more

important even than liberty, for they concern the inner life, the soul

and

eternity. Let us be strong and quit

ourselves

as men—strong in the strength of Jesus, strong in the presence of the

Lord of

Hosts. Let us, in all our efforts, in

all our successes, say unceasingly “Not

unto us, not unto us, Lord, be the glory.” Let

us in all our reverses still praise the

Lord and in all humility reply “Our God is in the Heavens: He hath done

whatsoever he pleased.”

|